I never expected to find comfort food when I stepped into this non-descript building of production plants and warehouses. Tonight, however, a veritable home-cooked dinner was laid out for me inside. Choi sum stir-fried with garlic, green beans stir-fried with black beans and chilies, a pork and potato stew and bowls of freshly harvested Yuen Long rice. As we ate huddled around a folding table in Fredie’s 2000-square-feet loft apartment, I began to digest the housing reality facing Hong Kong’s young generation today.

Although I was once a housing beat reporter, and am still proud of my ability to recount how the laws and policies in this area have changed over the years, my long chat with Fredie and his girlfriend Rachel Lee in the industrial building unit that he shares with four others made me realise I had under-estimated the difficulties confronting the young generation in their search for an affordable and decent home.

Because the city’s laws forbid people from living in industrial buildings, I promised my friend that we would not reveal any details which might lead to his home being located.

Fredie Chan became an independent filmmaker after he spent several years filming and producing current affairs programmes at Radio Television Hong Kong. An expert on moving images, he taught me what I had to consider about camera angle and distance in relation to the human subjects being filmed in order to give the material emotional weight.

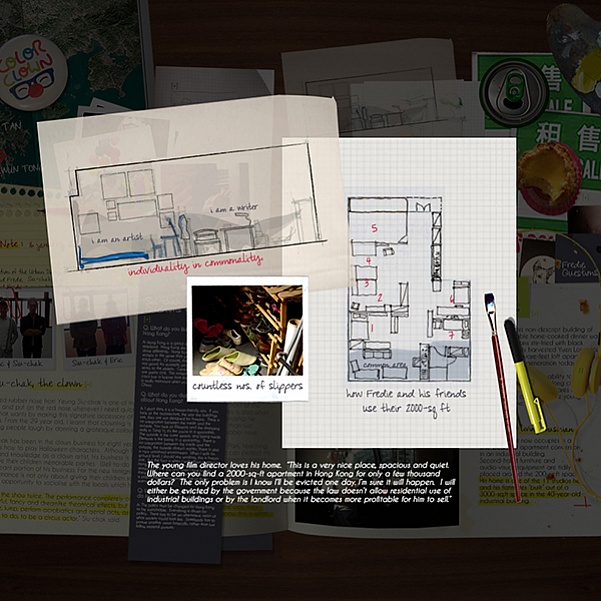

In this shared loft accommodation of five people, Fredie has a 100-square-feet private section which also functions as his studio. Furnishing in this wall-less and door-less bedroom is most basic. There are only seven pieces of furniture: a bed, two desks, two chairs, a bookshelf and a wardrobe. He uses the desks, the bookshelf and the foldable wardrobe to mark the bedroom boundary. “Packing will be a fairly simple task for you,” I said as I surveyed his corner.

“For me to run my business, I only need a camera and a computer; I don’t need any huge machine. In my case, work and living have been married. I believe, in fact, quite a number of people in Hong Kong have done the same so they don’t need a separate office. They either work at home, or live in their office. I think you should consider moving to a loft,” Fredie said.

The young film director loves his home. “This is a very nice place, spacious and quiet. Where can you find a 2000-sq-ft apartment in Hong Kong for only a few thousand dollars? The only problem is I know I’ll be evicted one day. I’m sure it will happen. I will either be evicted by the government because the law doesn’t allow residential use of industrial buildings or by the landlord when it becomes more profitable for him to sell.”

It’s true that Fredie can pack up his furniture quickly but it doesn’t mean he can find another loft if he has to move out. His rent is relatively low and sharing it with like-minded friends makes it possible for him to take up socially meaningful but unprofitable projects. Right now, he’s spending less than HK$2,000 a month on rent and other miscellaneous expenses.

While Fredie was preparing dinner, he kept asking me where else he could find decent accommodation as cheap as the loft he occupies. “Think about how much a young person earns nowadays, even if we live in a partitioned flat, it’s going to cost half of our monthly salary. Then we also have to give money to our parents. How much have we got left after paying rent and paying our parents? Many young people don’t get along well with their parents but they are forced to stay with their parents because they can’t afford to move out. I left home during my first year in college, my mum always says I should move back, but I have no plan to do so, I can’t live with my family again. But not everyone is like me, my loft mates, for example, some of them go back to stay with their parents regularly. They only come here for a break.”

Fredie stresses that he does not resist the idea of living in remote rural areas. “Do you think we can get a cheaper rent if the five of us move into a village house together, not just one floor of a house but the entire block?” Calling himself a community person, the big dinner he prepared was good for four people since he’s also cooking for one of this loft mates who usually eats dinner at home. If there are leftovers from the generous servings he cooks, whoever wants to bring a packed lunch to work the next day can take the food. The five residents of the loft apartment share their food and other resources, including their expertise. Fredie always turns to the musician loft mate for assistance when he needs original music scores for his films.

The loft has no partitions or walls. The residents use the few pieces of furniture they have to mark their boundaries. The furniture-built-boundaries form a wide corridor that bisects the rectangular shaped loft. Chairs, sofas, paintings, a bicycle, and other named and unnamed miscellaneous items lie scattered on two sides of the corridor.

Most of the miscellaneous items that are free for everyone to use, such as film set tools, are kept on a nearly three-metre-tall shelf that the residents patched together using unpainted wood pieces and iron bars. The self-made shelf stands near the entrance. Facing the huge shelf is the only room of the loft. Inside the room there are a number of second-hand musical instruments, including a piano, an electronic keyboard, a drum set, and several pieces of Chinese musical instrument. The room is where the musician fixes and records music. At the far end of the loft is their shared living room where they hang out, eat and watch DVDs.

Despite the constant uncertainty that he’s living in, Fredie prefers the government to leave the laws regarding the use of industrial buildings unchanged. He worries that if the government somehow relaxes the laws, a surge in demand – and rent – for the suddenly available spaces will follow, leaving him and other artists with nowhere to go.

Fredie grew up in a public housing estate in Tai Po and he likes public housing. “Public housing is good. I will have a place where I don’t have to worry about eviction. I know living in public housing nowadays means living in a place that’s even more remote than Tung Chung, but the location doesn’t bother me, I am home office.”

Fredie’s Q&A

Q:What do you like the most about Hong Kong?

A: Hong Kong still has grey areas where I can have fun, like industrial buildings where I can find cheap accommodation and farms in the New Territories where I can go to have a taste of farming. This generation of Hong Kong people can still enjoy these grey areas but I doubt if the next generation will have the same privilege. The government is moving very quickly, it wants to develop the remaining rural areas into new towns and encourages developers to redevelop industrial buildings. You have to substantially let go of your vanity if you want to enjoy the fun of these grey areas. Could you accept telling others that you’re living in an industrial building where manual workers go everyday to load and unload goods? After I moved into an industrial building, I started thinking where else can be turned into residences in Hong Kong.

Q: What do you dislike the most about Hong Kong?

A: The prevalence of greed and discontent. When you’re in secondary school, people make you think you have to go to university. When you’re in university, people make you think you need to do a part-time job. They also let you know they expect you start saving for a property once you graduate. When you have a property, they tell you that you have to wait for a good price to sell your property in order to make more money. When you’re a kid, your parents tell you these rules. After you grew up, you find out everyone’s behaviour is exactly what they were told to do over the years. The vicious cycle continues generation after generation. This belief gives people plenty of unnecessary pressure. The fact is none of these demands is related to our basic needs, whether we are happy, and if we engage ourselves in meaningful activities. Everyone is always thinking how they can make more money; they don’t have time to think how to do something meaningful, and how to satisfy their spiritual needs.

When I tell others I’d like to live in public housing, their reaction will invariably be: ‘But public housing is for those who genuinely need them.’ But what does ‘those who genuinely need them’ mean? Our public policy encourages young people to purchase property. Look at the income limits for public housing eligibility, do you really think people who are earning below the income limit can actually survive in Hong Kong? They have to wait for three years to get an allocation, you think a single can survive on slightly more than HK$9000 a month, or a couple can survive on some HK$13,000 a month? The government will expedite your case if you are chronically or mentally ill, or if you have a tendency to commit suicide. What does that mean? It means you have to tell others you’re mentally ill to get a quick allocation. When others know you’re mentally ill, no one will hire you and you’ll carry that label for the rest of your life.

Q: What does Hong Kong need to do for it to be a sustainable city?

A: We should stop this vicious cycle. If we can deal with people fairly, accept no exploitation and live a humble life. Living happily doesn’t actually need much.