When talking to the residents of Ap Lei Chau, there is a feeling that different eras of Main Street is embedded in their memories, dense and plentiful.

There were records of people settling in Ap Lei Chau Main Street as early as the Ming Dynasty. The Hung Shing Temple on the eastern shores of the island was built in the year 1773 (Qing Dynasty). Sometime between the Bubonic Plagues in 1894, the residents in Ap Lei Chau built a pair of fengshui pillars, safeguarding the fortunes of the island ever since.

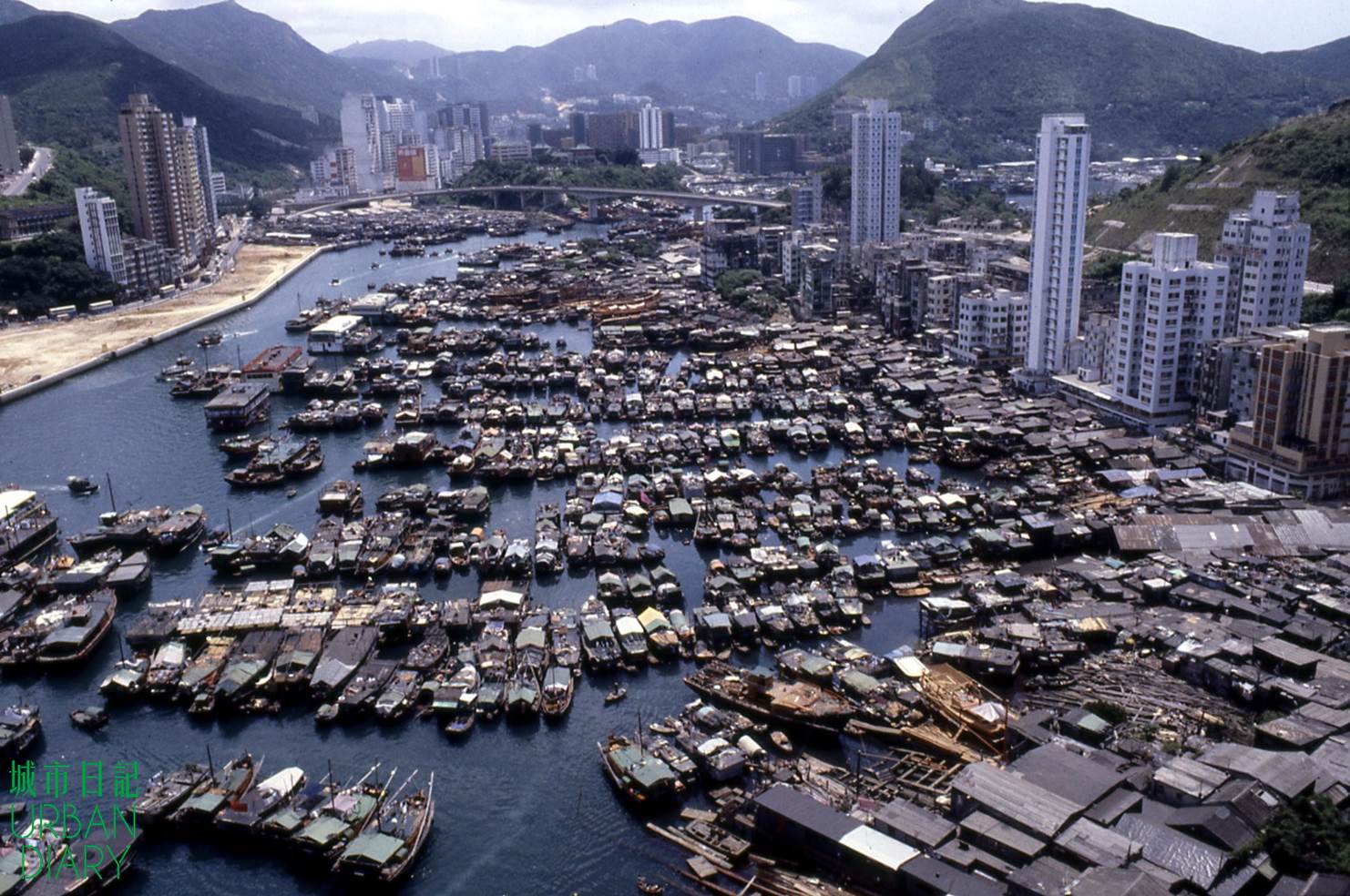

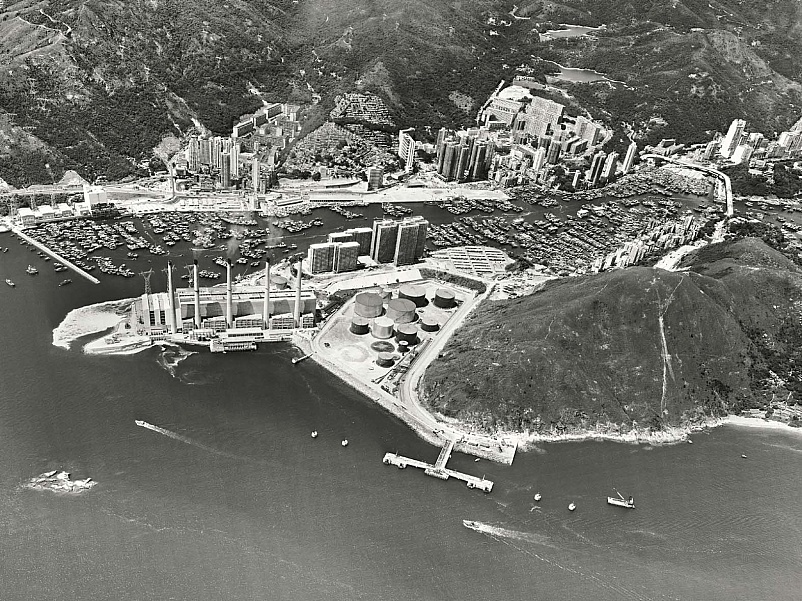

According to the kaifong, post-war Ap Lei Chau was a “no man’s land” because of a lack of land transport. Gambling stalls and drug sellers populated the area outside Wah Ting Street Recreational Area (soon to be MTR exit). Wooden squatters dotted the coastline outside Main Street, and later developed into a dense network of ship repairs and machineries. Soy sauce and noodle factories also occupied the hills on the west. The construction of the Ap Lei Chau Bridge in the 1980s transformed Ap Lei Chau into a peninsula of sorts. The development of public/private housing also brought incoming residents into the island en masse.

The Changing Northern & Southern Seas:

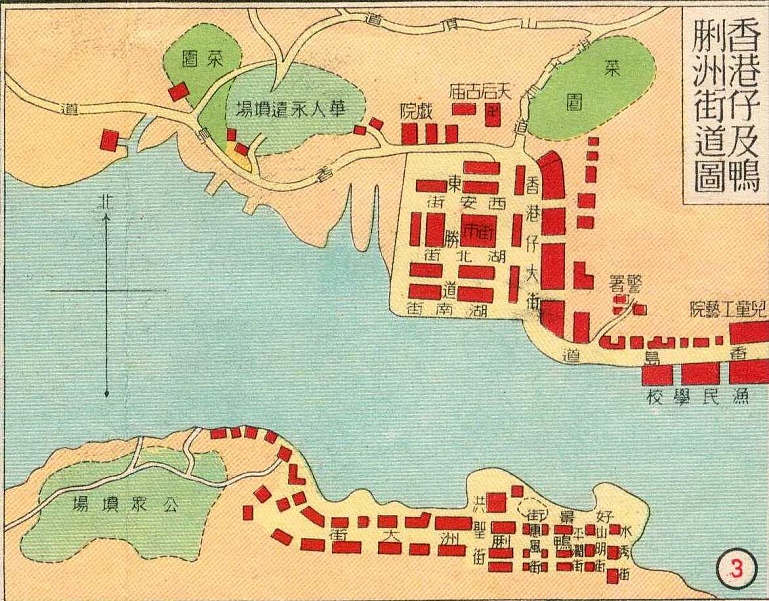

Ap Lei Chau Main Street underwent reclamation in 1950 and 1985 respectively. From a map drawn in 1950, we see that the sea is located right outside the Hung Shing Temple. The current Marina Habitat and Municipal Building used to be the sea. Back then, western hills used to be a public cemetery. According to Sin Pui On, people from all over Hong Kong came to worship their ancestors.

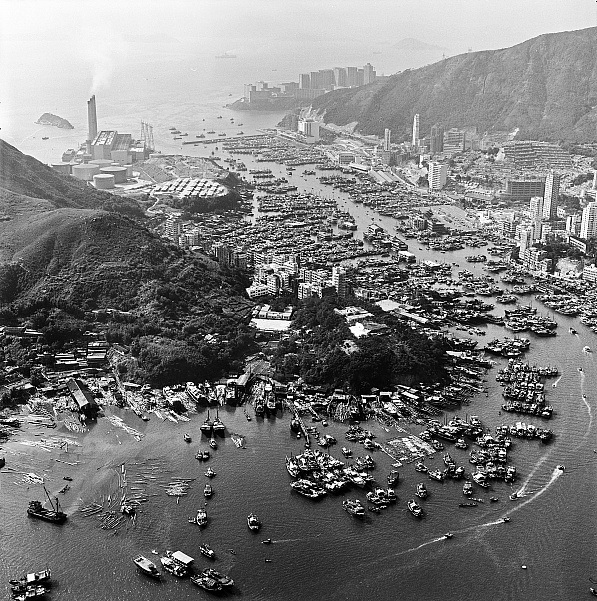

The boat people usually hail the Aberdeen shores as “north sea”, whereas Ap Lei Chau belongs to the “south sea”. “North sea” is the place for fish trading, and the purchase of ice and oil. “South sea” is the center of fish repairs, fishing tools, and entertainment. After selling their produce, the boat people spend their money in Ap Lei Chau. This is why older kaifong all point out that Ap Lei Chau used to be busier than Aberdeen.

Apart from the two seas, Ap Lei Chau residents divide the island into the eastern and western shores. With Main Street as the center, the eastern shores include the Ap Lei Chau Park, Sham Wan Towers, and Lei Tung Estate of today. On the other hand, the western shores refer to the Wind Tower Park, Ap lei Chau Estate, and South Horizons. As metal shop owner Kwok Siu Wing points out, the Ap Lei Chau Park of old was only a piece of barren land, “Ap Lei Chau Park used to be a barren ground used for drying fish, mending sails and playing games.”

Main Street has always been the economic center of Ap Lei Chau. London Lane, an alley adjacent to Yuet Hoi Street, used to lead towards the busy London Pier, which was located in today’s Marina Habitat. After the reclamation projects in 1985, the pier was demolished, and London Lane was also shortened. Similarly, Shan Ming Street and Shui Sau Street, a pair which together means “beautiful waters and hills”, became separated as Shui Sau Street was incorporated into Ap Lei Chau Park. Development has affected the community of Main Street. As Tang Kwok Ming, executive of Tung Hing Association, points out, the construction of Ap Lei Chau Park ignored the needs of the local community. It has also disrupted the fengshui of the island. Despite the boat people living on shore, fengshui is still of prime importance to the older generations of Ap Lei Chau.

Traditional Industries and Collective Memory:

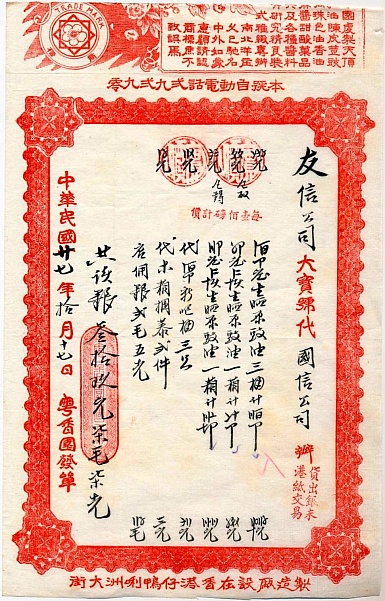

The dense population of Ap Lei Chau in the 1960s brought a steady supply of labor to the island. Traditional industries included: ship-making, ship repairs, machineries, soy sauce and noodle manufacturing, and paper sacrifices. The soy sauce and noodle manufacturers even exported their products to South-east Asia, whereas ship repairs and machineries mostly served the boat population.

Although the local machineries refused to hire local apprentices, the residents of Main Street worked in various industries. Kwok Siu Wing worked as an apprentice in a metal shop; Tang Kwok Ming helped out in his family’s ship repair business; whereas Lo Kam Kwan also helped out in his family rice shop.

Similarly, Gladys Cheng Wai Ling remembers how she helped out in Yuet Heung Yuen, a local soy sauce manufacturer. “Yuet Heung Yuen was located where the West Estate is. During high season, the workshop would hire many people to work. Everyone on Main Street would help peel gingers, and scoop out the lotus seed kernels. It was a great sight. I played my part as well to earn pocket money.”

As a place for residence and work, Main Street is witness to the skills and memories of a few generations of kaifong. This is perhaps the reason why its residents still call themselves “Ap Lei Chau-ers”. As the fishing industry migrates northwards, the traditional industries in Main Street have slowly hollowed out. Nowadays, the island still houses a few ship repair shops on the eastern and western tips, as well as some rice shops, metal stalls, and shops selling fishing tools on Main Street. Those who chose to continue business have their own tears and persistence. Metal shop owner Kwok Siu Wing chose to remain until he couldn’t afford the rent. Similarly, while rice shop owner Lo Kam Kwan is against the “preservation” movement of the younger generation, his family has refused to sell their shop, coincidentally halting the pace of redevelopment.

Community under Wheel of Development:

Throughout “Tales of Ap Lei Chau”, we witness the daily tension between the old and new. In recent years, Main Street has been hailed as the “Tsukiji of Hong Kong”, attracting tourists into the area. On the other hand, there are a handful of elderly homes on Main Street, offering a quiet quarter for its aging population. Today’s Ap Lei Chau features residential projects next to hundred year-old shops, as well as older generations next to incoming residents.

In face of a new round of urbanization, the younger generation of residents are concerned with the island’s prices, rent, and changing scenery. The recent protest over the upscaling of Marina Square West is an example of gentrification. The older generation, however, are more concerned with the island’s fengshui, transportation, and kaifong network. While criticizing how recent development has disrupted the island’s fengshui, more senior kaifong also hope to develop Ap Lei Chau’s tourism. There have also been recommendations to create a traffic bypass through Ap Lei Chau Park, solving the “dead-end” situation of Main Street.

The development of public housing and bridges in 1980s led to significant changes to the demography and ecology of Ap Lei Chau. The northward migration of fishing has further hollowed out the island’s industries. As the South Island Line is set to open, Ap Lei Chau faces a new round of urbanization. No one could say for sure what challenges its residential-based community would face. By re-tracing the older generation of stories about Ap Lei Chau, we hope to help imagine the plentiful future that lies ahead for the island.

References:

Chinese Temples Committee. "Hung Shing Temple, Ap Lei Chau" (http://www.ctc.org.hk/en/directcontrol/temple9.asp)

Ngo, Vivian. Mapping the History of Land Reclamation in Hong Kong. (http://www.oldhkphoto.com/coast/)