Foreword: History of Water Communities

It seems as if all stories about post-War Hong Kong begin from Shek Kip Mei. The influx of refugees during the civil war in China led to the boom of squatters across Hong Kong. A fire on the Christmas of 1953 consumed the wooden huts of Shek Kip Mei, leaving 50,000 homeless overnight.

The Shek Kip Mei Fire is often seen as a turning point for the housing and colonial policy of Hong Kong. This way of telling Hong Kong’s story, however, ignores the other people and communities in the city. In order to tell the story of Aberdeen, we need a history from the perspective of its water communities.

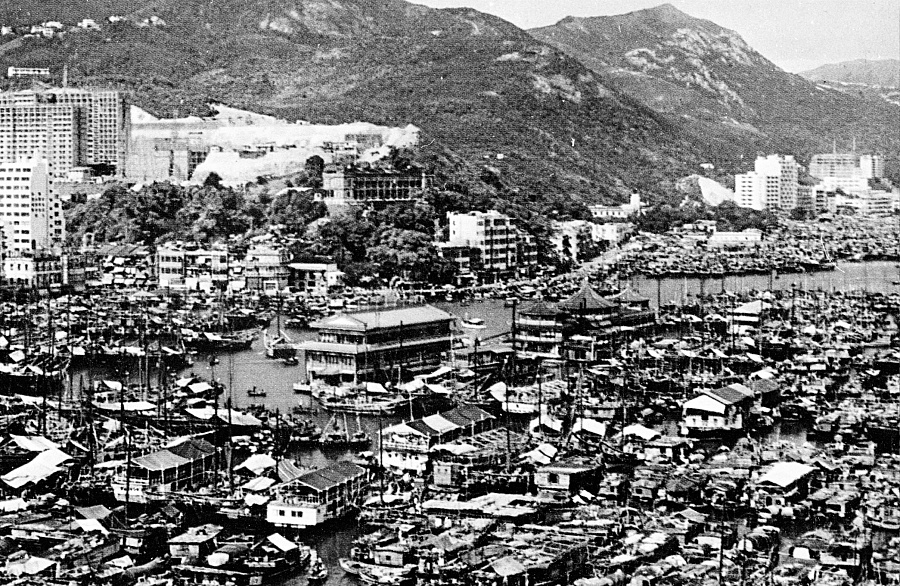

A textbook published in 1940 has the following description about Aberdeen: “Aberdeen is the largest fishing harbour on Hong Kong island. It is close to the sea but also has a hilly terrain. With its deep streams reaching inland, Aberdeen is comparable to Jiangnan. Ap Lei Chau is only 80 yards away from Aberdeen, the two places make up one single district.”

The historic portrayal of Aberdeen helps us trace its evolving terrain and coastline. The streams that reach deep inland, for instance, is something that has changed in subsequent years. Let us trace the post-War evolution of Aberdeen from the perspective of oral history.

Aberdeen 1.0: Fisheries Centre (1945 – 1970)

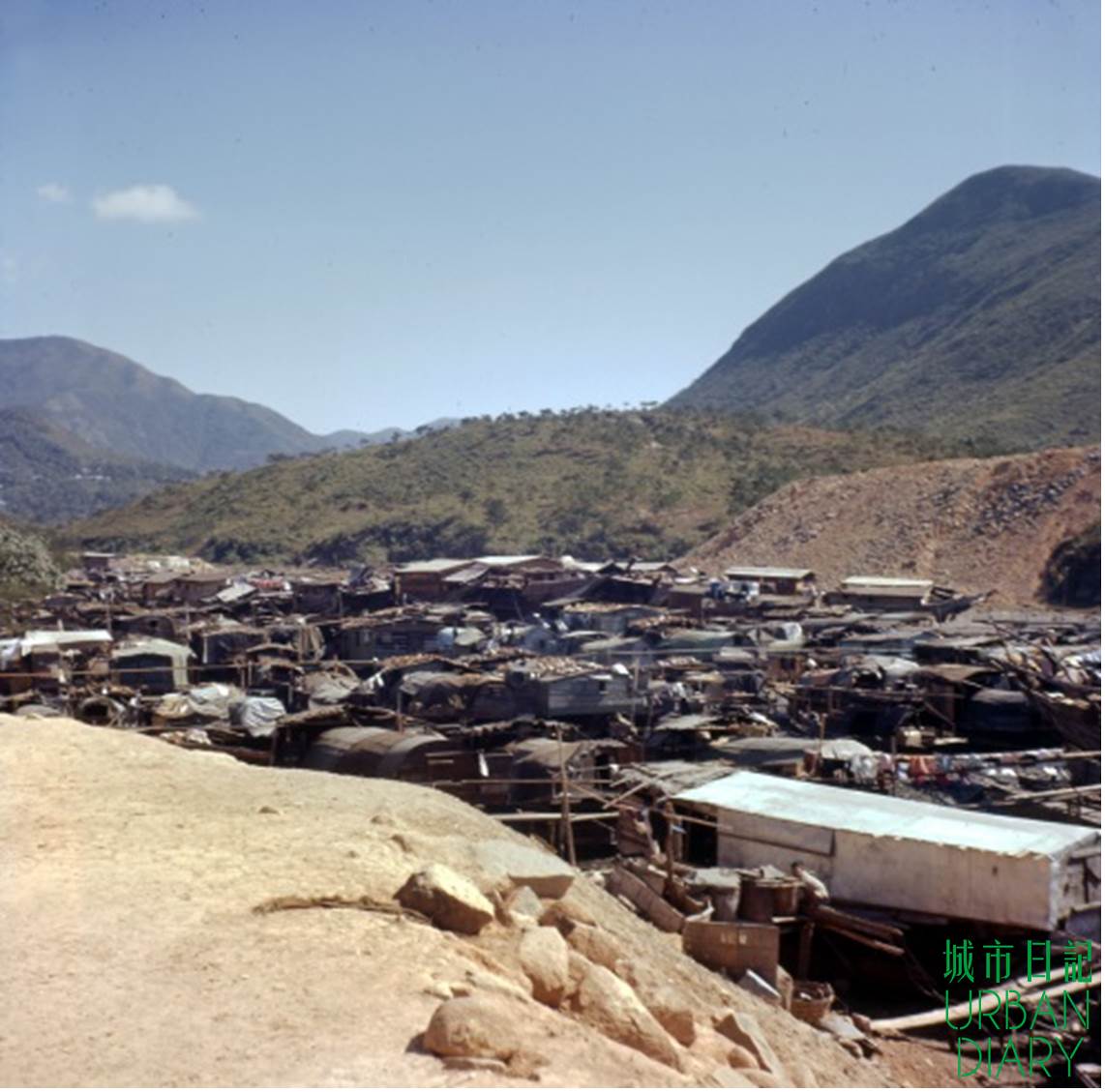

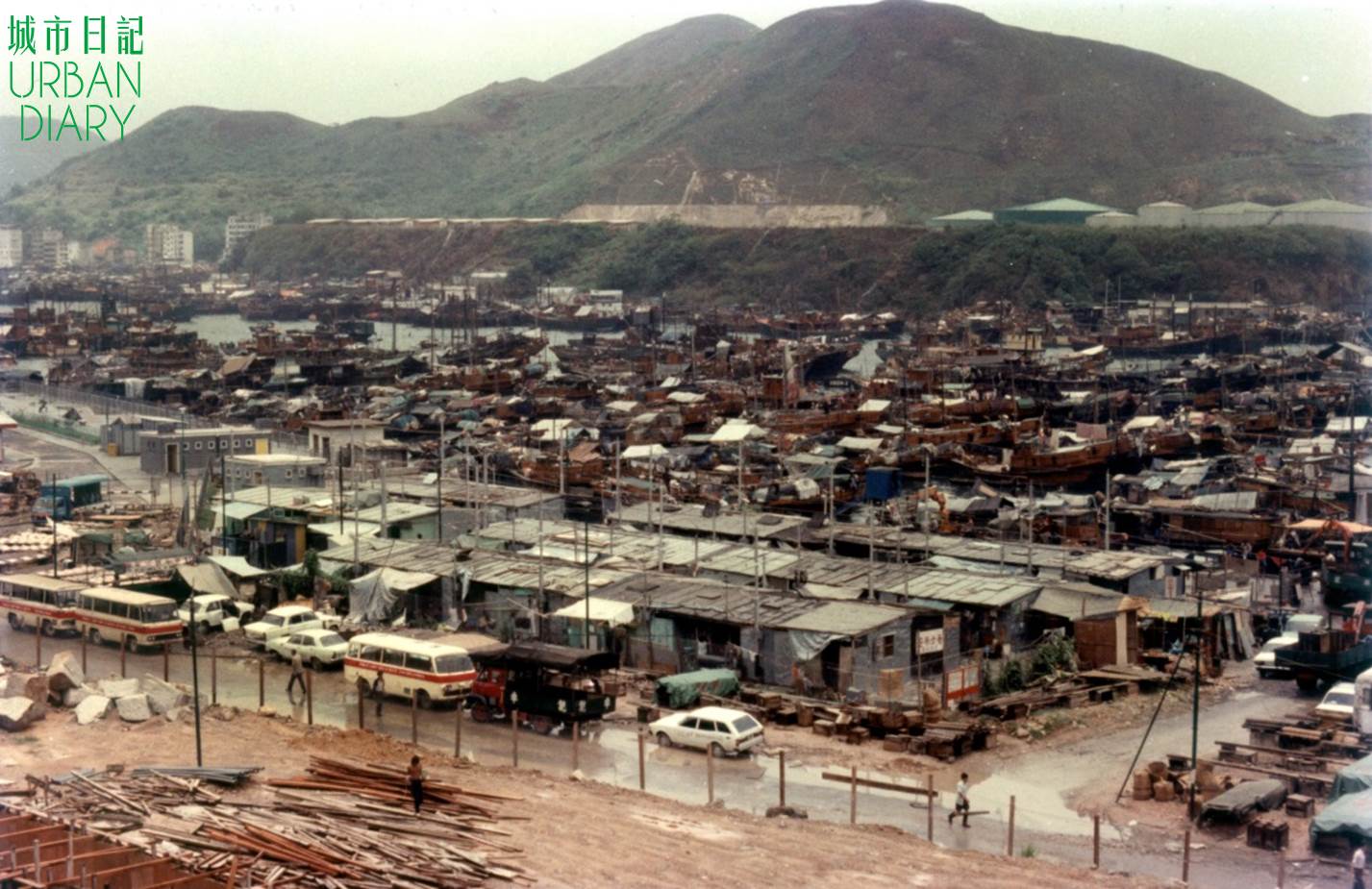

Post-War Aberdeen was a centre of fisheries and ship-building. Despite the lack of resources after Japanese Occupation, Aberdeen’s ship-building and fishing industries quickly got back on track after the War. According to a census on 1961, 90% of Aberdeen’s 30,000-strong people belonged to the fishing population. According to another survey in 1966, there were at least 45 ship-building yards in Aberdeen, the most in any region at that time.

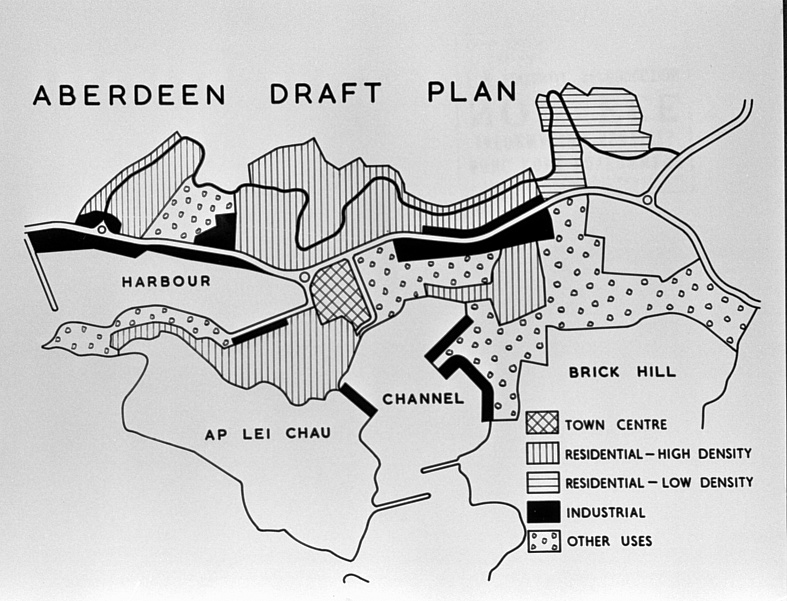

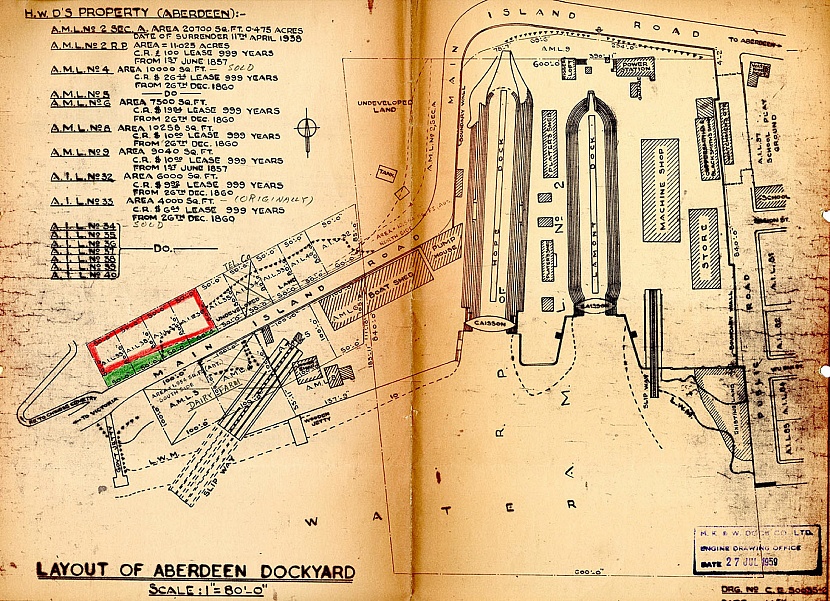

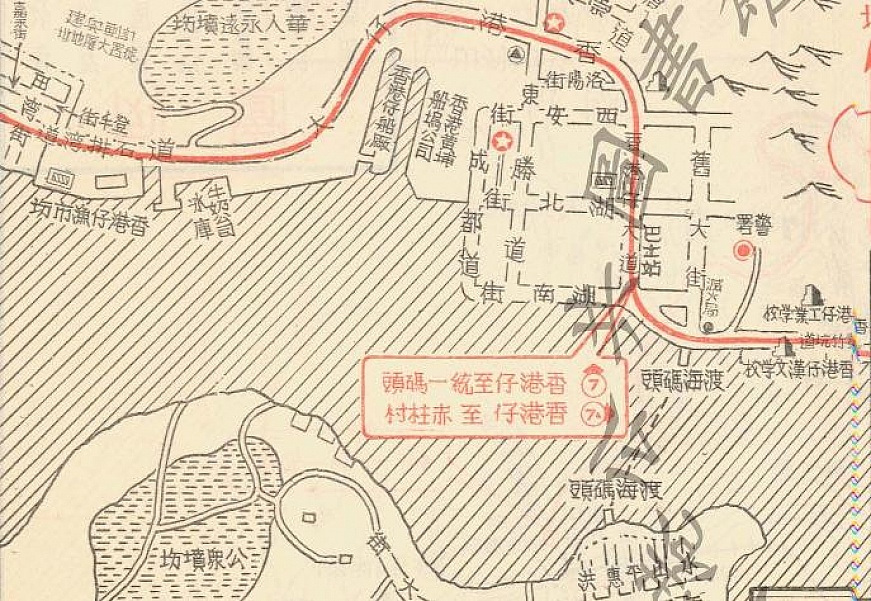

The water communities called Aberdeen the “North Sea”, while Ap Lei Chau was the “South Sea”. From a map produced in 1963, the North Sea housed important buildings such as the Aberdeen Fish Market, Dairy Farm Ice Factory, Aberdeen Dockyard, and Aberdeen Technical School. North Sea was the centre for fish, ice and oil trading. The South Sea was the node for boat repairs, fishing tools, and entertainment. The tea houses on both sides of the sea often competed with each other for customers.

Although the fishing population was quite mobile, the wars and conflict in mainland China led to the migration of fishing families from Guangdong to Hong Kong. For those who escaped to Aberdeen as refugees, 1949 was a sensitive year. James Chow Kee Chung, whose family used to live along the shores of Yangjiang, escaped with his family to Hong Kong from Communist influence. They settled initially around Grass Island before migrating to Aberdeen.

The vibrant fisheries and concentrated fishing population together molded the unique lifestyle of Aberdeen. For Palita Cheng Po Chu, who was born in a fishing family, the interconnected coastline was the best childhood playground, “We lived on the boat with my siblings and nephews, so imagine how many heads turned for a call! Back in those days, it was a half-hour walk to school from Chung Mei, passing by ‘Fifteen Houses’ (Sup Ng Gaan) and then marching along the Aberdeen Avenue (now Tin Hau Temple) to Tin Wan. In our spare time, my siblings and I would go on-shore and play in the soccer field in the Technical Institute. That was our entertainment.”

Chung Mei, close to today’s Aberdeen Technical School, is the intersection between Aberdeen Harbour and the streams of Wong Chuk Hang. “Fifteen Houses” (Sup Ng Gaan) refers to the walkway between Chung Mei and Old Main Street. It was so named because there were fifteen connecting houses along the walkway.

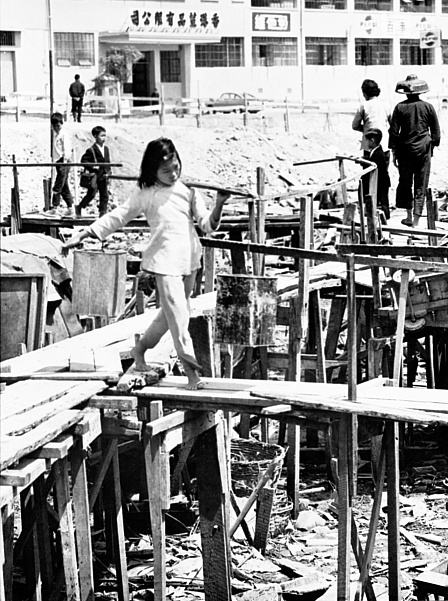

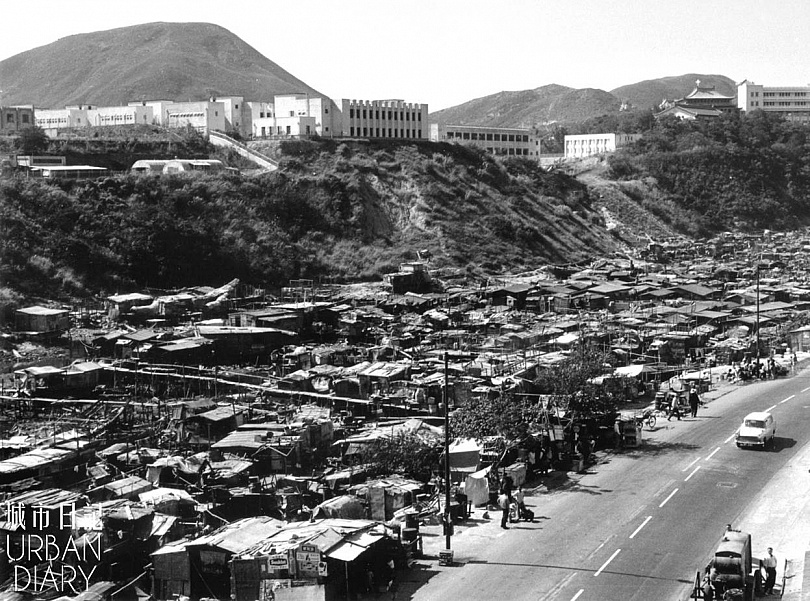

Spring 1960 saw a huge fire which spread across the boat squatters in Chung Mei. Because of the densely packed squatters, the firemen could hardly put out the fire. After the incident, the government began clearing Chung Mei, and the squatter families were moved to the neighbouring Tin Wan and Shek Pai Wan.

Aberdeen 2.0: Fishing Population Goes on Shore (1960 – 1990)

The Chung Mei Fire of 1960 symbolized the blow that urbanization struck on Aberdeen’s water communities. On the one hand, the family-intensive mode of fishing was replaced by improved technology and larger skills. The enforcement of compulsory education allowed the children of fishers to adapt to an on-shore lifestyle. By the 1980s, competition also came from mainland China, which further constricted the space of family operations. Lai Tai and Lee Ah Mui, for instance, remember how mainland fisher in Shantou chased them away by flinging glass bottles.

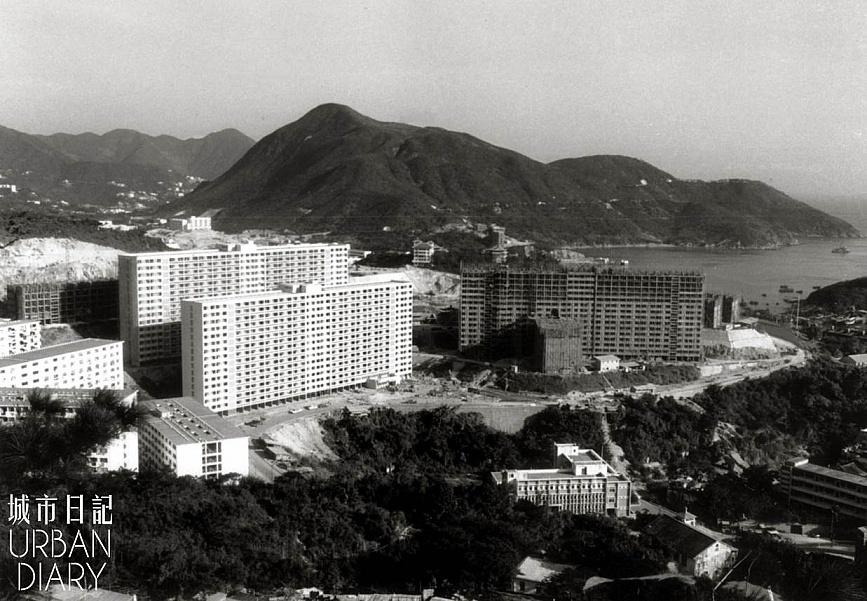

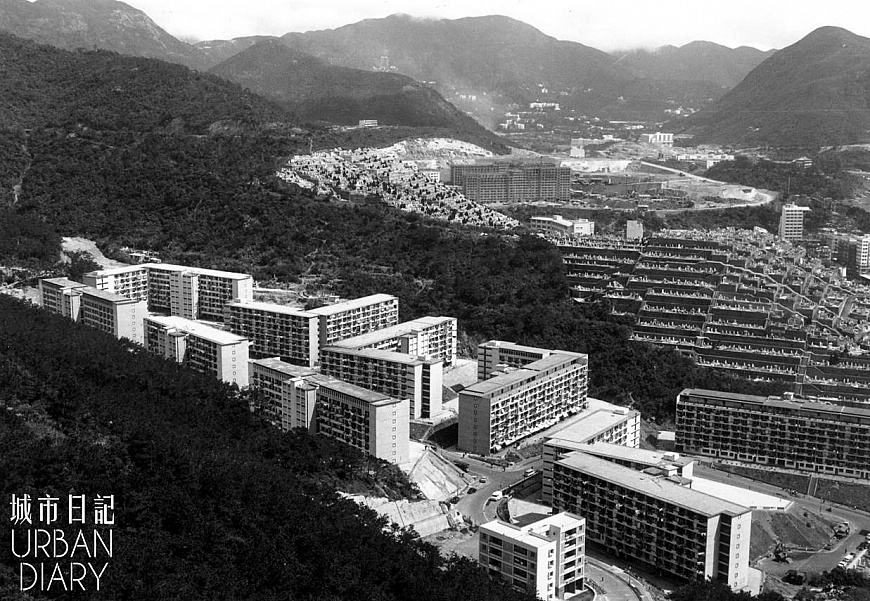

On the other hand, the government began reclaiming land in Wong Chuk Hang for industrial purposes. Soon, Wong Chuk Hang featured prominent factories in the beverage, food, printing, and drug-making industries. Similarly, public housing estates cropped up at a rapid pace in the 1960s, which brought a large outside population into Aberdeen. These changes further affected the water communities in the district.

The two decades between the Chung Mei Fire (1960) and Ap Lei Chau Boat Squatter Fire (1986) saw the rapid decline of boat people. Modernization brought with it safer, more stable living quarters; but it also stripped the water communities of their original mode of life. As it has been pointed out, the fishing people went on shore because of changing circumstances and government policies. “The Government . . . stripped the fishing community of its sustainable space and lifestyle. The boat and squatter people felt the pressure of a modernized fishing industry, there was no way to go except on shore.” (Quoted from “A Story about Water Families”)

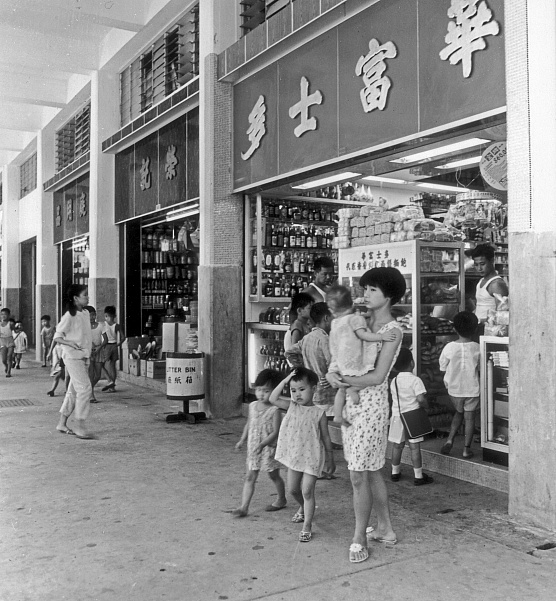

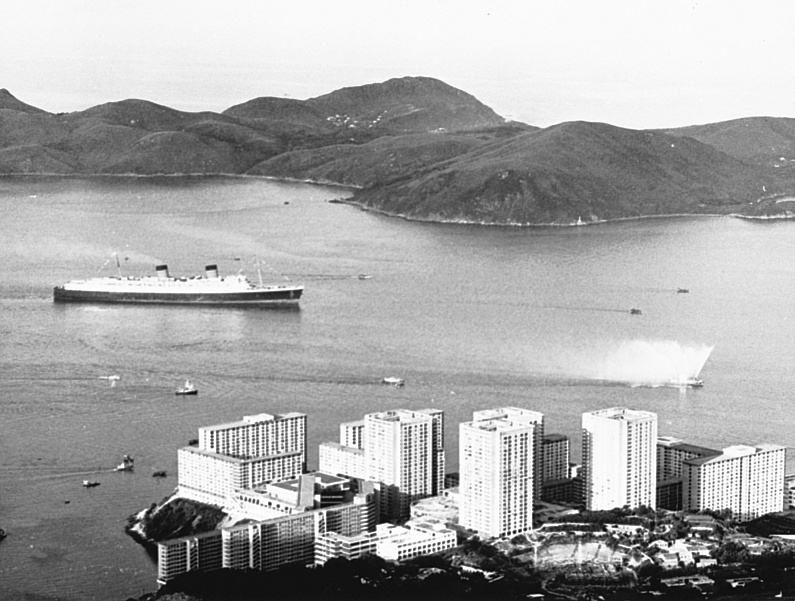

The boat people’s route on shore contrasted with the freedom of the public housing population. Public housing estates like Wah Fu drew a huge outside population into Aberdeen. In order to attract more residents, the government shot a promo named “Wah Fu New Estate” in 1968. The promo included the image of a woman watering flowers on a balcony with a view of the sea. Designed by government architect Donald Liao, Wah Fu Estate was the first housing estate with a cohesive vision of town planning. Playgrounds, eateries, markets, banks and other public spaces nurtured the growth of a generation of Hong Kongers. As Teresa Lo recounts, “Wah Fu Estate feels like “Penguin Village” (à la Dr. Slump). It is a peaceful estate free from outside interference. Daily needs from clothing, groceries to transport could be met inside the estate.”

Under the “history” section of the Hong Kong Tourism Board, there is a phrase to the effect of, “We will inform you the story of Hong Kong’s development from a fishing village to a cosmopolitan city”. Yet, the idea of “development” could not entirely capture the toil and dreams of a few generations of Hong Kongers.

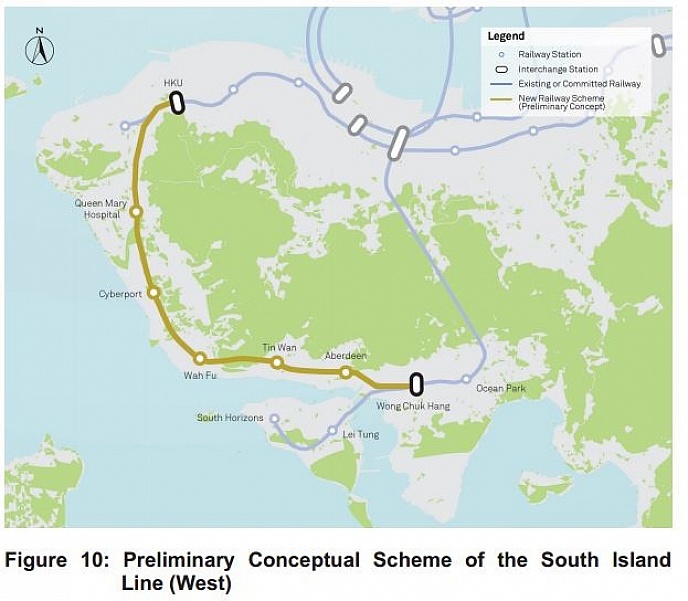

Aberdeen 3.0: Latest Round of Development (1990 – )

Aberdeen today is the result of five decades of urbanization and reclamation. We can get a sense of Aberdeen’s latest development by looking at Wong Chuk Hang and Wah Fu. After the 1980s, the northward migration of industries led to the emptying of Wong Chuk Hang’s industrial buildings. Yet, in the last ten years, art spaces and galleries such as Blindspot and Spring Workshop have made use of these empty spaces to foster a small but vibrant art cluster. As art critic John Batten points out, however, the honeymoon period between industrial migration and commercial growth has since come to an end, “The funny rhythms of Wong Chuk Hang are still there. But it's a little bit different than it used to be. That's inevitable. Just by changing a few things, you change a whole community.”

The “revitalization” of industrial buildings has led to increased rents for galleries and art spaces. The emergence of Global Trade Square and One Island South have further sped up the district’s growth in hotels and dining spaces. The dissonance between an old industrial area and a new commercial area is upsetting for someone like Roy Hui, “In my mind, industrial buildings are places for the working-class people, factories, and printers with their machines and ink. In Sing Teck Factory Building where I go to work, there is now a fancy restaurant serving Western cuisine. Foreigners and nicely dressed people are attracted to our building. I feel that industrial buildings are no longer industrial.”

References:

Heung, Wai-kin. Metamorphosis of Floating Community in Aberdeen. Hong Kong: University of Hong Kong, 1997. M.L.A. Thesis.

Leisure and Cultural Services Department & Hong Kong Jockey Club Charities Trust. Hong Kong Memory. (http://www.hkmemory.hk/index.html)

Ngo, Vivian. 香港歷史填海地圖Mapping the History of Land Reclamation in Hong Kong. (http://www.oldhkphoto.com/coast/)

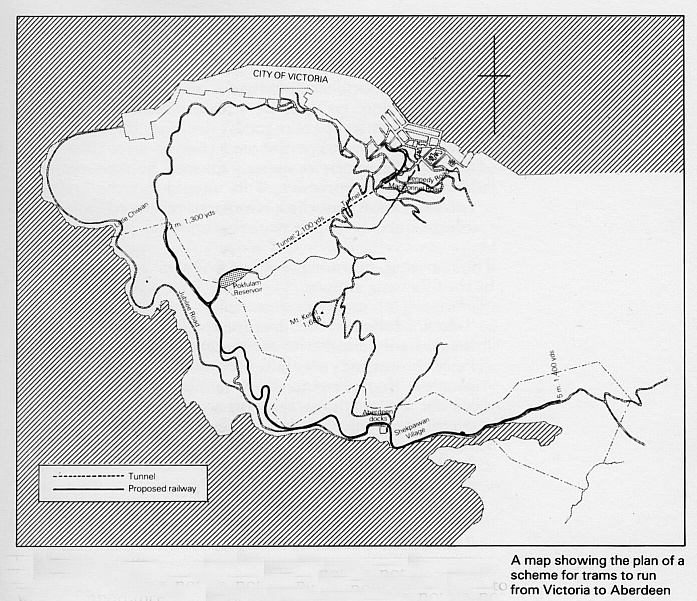

The Industrial History of Hong Kong Group. “Proposed Tramway linking Victoria and Aberdeen by Peak Tunnel, 1906-1910”. (http://industrialhistoryhk.org/chevalier-pescio-tram-linking-victoria-aberdeen-2/)

The Shipbuilding and Ship Repairs Industrial Committee. The Manpower Survey of the Shipbuilding and Ship Repairs Trades. Hong Kong: Government Printer, 1966. Print.

鄭錦細。The Story of a Water Community「一個水上家庭的故事:從水上人空間運用的生活文化尋找被遺忘的歴史」(https://www.ln.edu.hk/cultural/programmes/MCS/Symp%2012/S3_P2.pdf)

蘇子夏(編)。Hong Kong Geography 《香港地理:山海依舊風物在》。香港:商務印書館有限公司,2015。

梁智鵬、黃君健(編)。The Story of Wong Chuk Hang《黃竹坑故事:從河谷平原到創協坊》。香港:三聯書店有限公司,2015。

王惠玲、羅家輝。Memory Landscapes: Oral History of Aberdeen Fishers《記憶景觀:香港仔漁民口述歷史》。香港:三聯書店有限公司,2015。

梁炳華。The Heritage of Southern District《南區風物志》。香港:南區區議會,2009。